Six months before she died, in October 2021, former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright published a memorable essay in Foreign Affairs, “The Coming Democratic Revival.” Amid rising pessimism about the future of democracy, Albright, who was a friend of mine, offered a hopeful counterpoint. Authoritarianism was brittle and self-defeating, she argued, whereas the desire for freedom and accountability remained universal. “Democracy is not a dying cause,” she wrote. “It is poised for a comeback.”

As Albright saw it, authoritarian regimes were faltering and alternative models—especially those offered by China and Russia—were losing credibility. With democracy retaining its appeal, young people increasingly engaged in politics and connected with the world, and democratic institutions and civil society organizations strong and widespread, the global balance would tilt back toward freedom, especially if the United States were to step up its support of pro-democracy movements.

Nearly four years later, the comeback has not happened. Democracy, instead of surging, has faltered. In many places, it is in sustained retreat. Protest movements from Tbilisi to Tunis have faced crackdowns. Autocratic leaders old and new have more brazenly consolidated power, often under the cover of law. And in Washington, the second Trump administration has reduced U.S. support for democracy abroad while backing away from the norms and institutions that foster democracy at home.

This change in the United States may be the most consequential development of all. Albright warned that if the country abandoned its commitment to democratic values, it would embolden autocrats, betray allies, and diminish its own global standing. Yet the inherent weakness of authoritarianism remains. The legitimacy of an autocratic government is shallow: it depends on coercion rather than consent. Meanwhile, democratic ideals rooted in human dignity, equality, and empowerment are visible in street protests, underground classrooms, and encrypted chat rooms. Democratic movements need more support if they are to turn their aspirations into reality. But as long as these ideals endure, Albright’s hope for a comeback remains alive.

NO ILLUSIONS

Autocrats “are now failing to deliver,” Albright wrote, “including in countries where people increasingly expect accountable leadership even in the absence of democratic rule.” She argued that discontent would eventually erode the foundations of authoritarian regimes and create space for democratic resurgence.

For a time, Iran and Cuba appeared to offer that possibility. Both were governed by aging leaders of revolutionary movements whose founding myths had long since lost their hold. In Iran, decades of economic crisis, repression, and moral policing culminated in 2022 with the death of Mahsa Amini, a young woman detained for violating the country’s dress code. Her killing ignited a nationwide uprising led by women and students who openly denounced the regime and its supreme leader. For a moment, it seemed that Albright’s prediction was coming true.

That hope proved misplaced. The Iranian government crushed the protests with Internet shutdowns, mass arrests, and public executions. Today, as Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei reaches his late 80s, hard-line figures from the security services—not reformers—appear most likely to inherit his system.

The legitimacy of an autocratic government is shallow.

Cuba once seemed just as close to a turning point. In July 2021, the island witnessed its largest demonstrations in decades, as thousands demanded not only food and medicine but freedom itself. Those protests, too, were swiftly silenced. The government restored control through arrests, intimidation, and digital surveillance; many activists remain in exile or in prison.

The experiences of Iran and Cuba showed that authoritarian fragility is not the same as democratic opening. Regimes that fail their citizens can still adapt, using fear, technology, and force to outlast popular movements.

In an earlier era, the United States might have amplified dissident voices, supported independent civil society organizations, or imposed costs on repressive governments through diplomatic isolation and targeted sanctions. Today, the U.S. government is itself attempting to chill dissent at home while dismantling or defunding the tools Washington once used to support democrats abroad—and often aligning with authoritarian leaders instead. Without international solidarity and sustained outside pressure, protest movements face steeper odds in turning moral courage into political change. So even as authoritarian regimes lose legitimacy, they remain entrenched.

LOSING APPEAL

In 2021, Albright also pointed out that the world’s leading authoritarian countries, China and Russia, had failed to offer a compelling model for others to follow. They had an opportunity to present themselves as credible alternatives to liberal democracy during the first Trump administration, but “they blew it.”

That assessment has held up, in part. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine shattered any remaining illusions of benevolent strongman rule. China, meanwhile, has struggled to present a convincing alternative. Its once vaunted economic miracle has slowed sharply, and across much of the developing world, Beijing is now viewed less as a partner than as a predator—a creditor wielding debt, infrastructure, and technology to entrench dependence. China’s surging youth unemployment and tighter political controls have further undermined its image as an efficient, technocratic autocracy. Surveys from Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, meanwhile, show that publics in regions most exposed to Chinese influence still express clear preferences for democratic governance over authoritarian rule.

The United States, however, is voluntarily ceding ground. The dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the defunding of Radio Free Asia and Radio Free Europe, the slashing of over $54 billion in foreign assistance, and the termination of more than 5,800 democracy-related programs have sent an unmistakable signal that Washington’s priorities have shifted.

This has given China an opportunity to portray itself as a more stable and pragmatic—and less judgmental—partner. Chinese officials now speak the language of “win-win cooperation” and “development without interference” as they engage governments around the world. In December 2023, Beijing eliminated tariffs on imports from the world’s 43 least-developed countries; this year, Washington has imposed steep tariffs on some of the same countries and suspended health, education, and food security programs there. Chinese firms have stepped into critical infrastructure projects, many of them in sub-Saharan Africa, that were once funded by the United States. Insisting on noninterference, Beijing offers foreign leaders capital and legitimacy without requiring transparency, human rights safeguards, or competitive elections—a model that strengthens incumbents and dulls democratic accountability.

ALIVE IN SPIRIT

“Despite the battering that democracy has endured,” Albright wrote, “most people want to strengthen, not discard, their democratic systems.” That remains true. In a 2025 survey conducted by Freedom House, 75 percent of respondents across 34 countries said they preferred democracy over other forms of government. This level of support has remained remarkably consistent despite years of democratic erosion. (I serve on the Freedom House board of trustees, which I formerly chaired.) Afrobarometer’s 2025 flagship report, drawing on surveys in 39 African countries, found that roughly seven in ten citizens still prefer democracy to any other form of government, and solid majorities support competitive elections, presidential term limits, and independent courts—even in countries that have experienced recent coups.

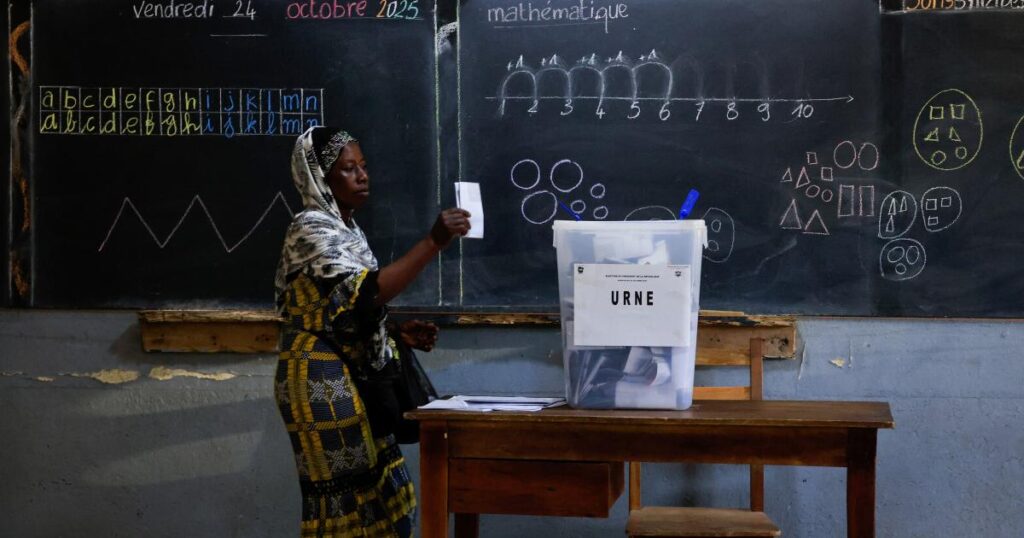

This democratic spirit is not confined to opinion polls. It has brought people to the streets. In Georgia, thousands of protesters—including students and civic leaders—have turned out in Tbilisi since the October 2024 parliamentary election, which international observer missions, including those from the European Parliament and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, determined was deeply flawed and had failed to meet democratic standards. In Israel in early 2023, before October 7, one of the largest protest movements in the country’s history saw hundreds of thousands take to the streets week after week to oppose a proposed judicial overhaul that would have severely weakened the independence of the Supreme Court. Israelis across ideological lines stood side by side to defend democratic norms.

In some places, resistance has come with high costs. In Myanmar, following a military coup in 2021, pro-democracy activists have endured relentless persecution. More than 4,000 people have been killed and over 25,000 imprisoned by the junta. In Tunisia, a country once hailed as the lone success story of the Arab Spring, President Kais Saied has dismantled a decade of democratic gains: dissolving Parliament, rewriting the constitution, and jailing his critics. In Belarus, the government has maintained a brutal campaign of repression. Nearly all leading opposition figures are in prison or exile, including the 2020 presidential challenger Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who was forced to flee Belarus after an election widely condemned as fraudulent.

THE PROMISE OF YOUTH?

Albright placed particular hope in the rising generation of globally connected youth. This cohort, she noted, was better educated and more demanding of accountability than any before it. Young people with “an ingrained belief in their own autonomy” would be more willing to disrupt the “traditional hierarchies” that prop up authoritarianism.

The energy of youth movements remains powerful, but it has been less transformative than Albright envisioned. In Chile and Colombia, youth movements were instrumental in electing reformist governments in 2021 and 2022, respectively. In India, young voters and digital activists have helped drive opposition organizing as the government grows increasingly repressive. But elsewhere, youthful idealism is colliding with institutional decay.

In Tunisia and Turkey, where checks and balances have eroded, courts have been politicized, and opposition parties face systematic harassment, young people are voting with their feet. A 2024 report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found a 12 percent increase in asylum applications by 15- to 29-year-olds across EU countries between 2021 and 2023, with notable surges from democracies in retreat—including Tunisia, Turkey, and Venezuela, whose increases were well above the continental average. In countries such as Egypt, Iran, and Myanmar, youth-led protest movements have been met with digital surveillance, online harassment, and mass arrests designed to intimidate, isolate, or drive out dissenters.

Even in relatively open societies, civic spaces are shrinking and democratic institutions are under pressure, leaving many young people excluded from meaningful participation. They are invited to vote but not to govern. Their expectations are rising, but their opportunities to shape outcomes are not. As the Arab Spring demonstrated, it is easier to topple a government than to build one, and the failure to convert protest energy into lasting democratic institutions has bred cynicism among the very generation Albright once saw as democracy’s best hope.

SUPPORT SYSTEM

Albright emphasized the enduring importance of democratic infrastructure—courts, legislatures, independent watchdogs, and electoral commissions—as tools for public accountability, even in illiberal environments. And she understood that democratic resilience does not happen in isolation. It depends on global networks that provide expertise, funding, and moral support, especially when local governments turn against their citizens.

For decades, that scaffolding has included both governmental and nongovernmental efforts. The National Endowment for Democracy, founded by the U.S. Congress in the 1980s with bipartisan backing, has supported civic actors, labor unions, journalists, and party-builders in more than 100 countries. Cross-border networks of pro-democracy political parties have offered not just ideological inspiration but real material and strategic assistance. The European Union and countries including Canada, the Nordic states, and others have helped train election observers, bolster media freedom, and sustain civil society watchdogs in environments where democratic space is closing or where activists operate under authoritarian pressure.

Democratic resilience does not happen in isolation.

These efforts have made a difference. In Poland, years of European pressure to uphold judicial integrity and electoral transparency helped enable the 2023 opposition victory over the illiberal Law and Justice party. Tunisian democracy thrived for nearly a decade—before its recent unraveling—in part because of consistent international investment in transitional justice, constitutional reform, and civil society.

But these successes are growing harder to sustain. According to Freedom House, nearly 60 countries experienced democratic backsliding in 2024 alone. That year, in Thailand, the Constitutional Court dissolved the leading opposition party. In El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele eliminated term limits and gutted judicial independence. Georgia’s new law targeting foreign-funded nongovernmental organizations, including many democracy-supporting organizations, imposes burdensome reporting requirements meant to silence dissent.

The Trump administration’s defunding of the United States’ democracy assistance architecture has made the work of activists around the world even more difficult. In addition to sweeping cuts to USAID and the National Endowment for Democracy, the administration has ordered the closure of the U.S. Institute of Peace and replaced the board and president of the Wilson Center (which I led for a decade), two institutions that convene policymakers and provide platforms for scholars and democratic civil society. Smaller donors and philanthropic networks have tried to fill the gap, but they lack the scale of U.S. government investment. Programs that once helped train election monitors, support investigative journalists, and connect grassroots organizers across borders are now running on fumes or shuttered entirely.

A REVIVAL DEFERRED

The vision Albright put forward in 2021 was hopeful but not naive. She understood that democracy would not rebound on its own. What she believed, and what she challenged others to believe, was that the desire for dignity, freedom, and accountability remained universal. That is still true. What has faltered is the infrastructure, solidarity, and leadership needed to translate that desire into durable political gains.

Albright believed that supporting democracy is not just a moral imperative but a strategic one. Authoritarian regimes do not simply repress their own people; they export corruption, weaponize information, and erode the norms that underpin global stability. Democracies make better partners. They uphold the rule of law, respect borders, and are far less likely to provoke conflict. And in the long-term competition with China, the United States’ greatest advantage is the attractiveness of its ideals, which help it build international coalitions, bring talent and investment into the country, and confer a legitimacy on the U.S. government that coercion cannot buy.

Albright ended her essay with a call for democratic governments to “band together to deliver on their promise, to counter their adversaries, and to support their defenders.” The democratic project has since suffered serious blows, but it is far from dead. The foundations of a revival remain to be built on when the world’s democracies—most of all the United States—muster the will to prevail.

Loading…