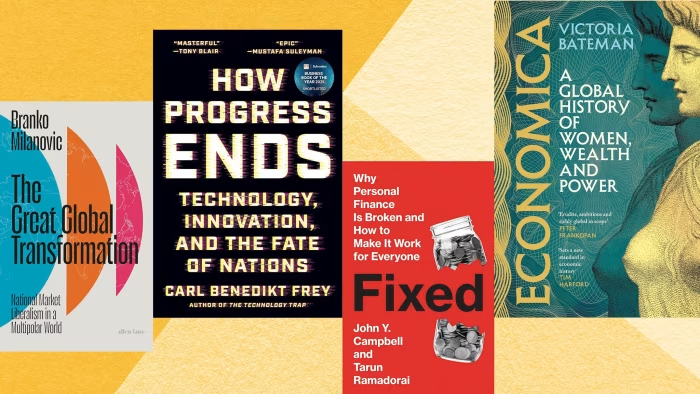

Economica: A Global History of Women, Wealth and Power by Victoria Bateman (Headline/Seal Press)

Women have always played a central role in the human economy. Yet many societies, contemporary Afghanistan being a hideous example, have tried to sequester and exclude them. The result of such efforts has always been disastrous, argues Bateman, a feminist historian, in this thought-provoking book. She puts the story right, from the Stone Age to today. The far greater economic freedom of women in the contemporary west is, arguably, our most important economic and social advance. Yet, as Bateman warns, “some of the most unequal societies today are ones in which women were once relatively equal, meaning that equal opportunities can never be taken for granted”. Indeed!

Eclipsing the West: China, India and the Forging of a New World by Vince Cable (Manchester University Press)

Cable has been a development economist, chief economist at Shell and a minister in the UK coalition government under David Cameron. He brings all his knowledge, experience and common sense to this book, which is on the defining political and economic issue of our era: relations between the west and the rising Asian giants, China and India. Cable suggests three possible future scenarios: a democratic “Global West” confronting autocratic adversaries, led by a failing China, with India joining the democracies; a multi-polar world, with a rising China and a rising India and no hegemon; and a multilateral world, with a reformed, but functional, postwar order and, again, no hegemon.

Fixed: Why Personal Finance Is Broken and How to Make It Work for Everyone by John Y Campbell and Tarun Ramadorai (Princeton)

This book would be the ideal present for anybody who needs lessons in finance. The authors, professors at Harvard and Imperial College respectively, are informed critics of a system that fools its users. “The problems of today’s financial system can be summarized as complexity and cost,” they explain. These two defects are related since “complexity increases costs to consumers”. A better financial system would, they argue, adhere to four principles: simple, cheap, safe and easy. With modern information technology, they add, these requirements could be met relatively easily. They recommend, in particular, creation of a “starter kit” for beginners.

Money and Inflation at the Time of Covid by Tim Congdon (Edward Elgar)

I admire Congdon. He has stuck to his monetarist principles, however unfashionable, through thick and thin. On at least two occasions they have made him spectacularly right when conventional wisdom was just as spectacularly wrong — the “Lawson boom” in the UK of the late 1980s and the post-Covid inflation. On both of these occasions, happily, he influenced me, too. He is right that money continues to matter. He is also right that the relevant money is “broad money”, namely, money in the hands of the public. This excellent book is his “I told you so”. Alas, conventional wisdom continues to ignore what he knows.

Why Nothing Works: Who Killed Progress — and How to Bring It Back by Marc J Dunkelman (PublicAffairs)

America was once a country that built things. Now it cannot. This is true in other high-income countries, too, including the UK. A big part of the problem is, as Klein and Thompson also argue (see below), that “progressives” have become ultra-conservative, even reactionary. One of the explanations, argues Dunkelman, is their intense suspicion of power and those who wield it. The resulting plethora of checks on power paralyses government. As he writes, “Lionizing government and then ensuring it fails is, in the end, among the worst of bad political strategies.”

Violent Saviours: The West, the Rest, and Capitalism Without Consent by William Easterly (John Murray/Basic Books)

Easterly stands alone among almost all development economists for his belief in human agency. The alternative, he argues, is violent coercion. Although often argued to be for the betterment of its victims, colonialism was just such coercion. Moreover, he insists, much of contemporary thinking on economic development also rests on a not dissimilar belief in the right to exercise coercive control. If agency and development are to be combined, he argues, the true answer must be commercial freedom — the right of people to trade freely with one another. Easterly’s commitment to liberal ideals is powerful.

How Progress Ends: Technology, Innovation, and the Fate of Nations by Carl Benedikt Frey (Princeton)

Frey, who teaches at Oxford, is a world-leading expert on the sources and consequences of technological progress. In this important book, he analyses the (to his mind, overhyped) impact of artificial intelligence and, more broadly, the prospects for future economic growth. His core argument is that “Innovation demands breaking rules, but efficient execution relies on following them.” Balancing these two requirements — rule-breaking and rule-following — is very difficult. Today, in fact, a loss of innovative capacity threatens China and the US, though for somewhat different reasons.

The World at Economic War: How to Rebuild Security in a Weaponized Global Economy by Rebecca Harding (London Publishing Partnership)

Harding is a well-known trade economist who heads the Centre for Economic Security. This book addresses a fundamental question for the UK, which is how to define and defend its economic security. We are, she argues, living in an era of strategic economic competition, “which is now tantamount to economic warfare”. The major players, China and the US, are able to employ formidable economic weaponry, as the trade wars of 2025 have demonstrated. Neither is self-evidently either reliable or friendly. Meanwhile, the UK and its European allies mostly have limited fiscal headroom. This is a tough new world. Navigating it requires a changed mindset.

A Sixth of Humanity: Independent India’s Development Odyssey by Devesh Kapur and Arvind Subramanian (HarperCollins)

In this compelling book, Kapur, a distinguished political scientist, and Subramanian, former chief economic adviser to the Indian government, analyse India’s modern history. They note that after independence in 1947 India “embarked on four major development transformations: rebuilding the State, forging a nation, developing the economy and reconstructing society . . . Crucially, this was to be undertaken under . . . universal franchise-based democracy.” This was a colossal undertaking. How did it do? My answer would be “far better than it might have and not as well as it could have ”. To work out your answer, read this book.

Abundance: How We Build a Better Future by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson (Profile/Avid Reader)

This is an important book that is just as relevant to the politics of Europe (including the UK) as to the US. We have, it argues, abandoned the free-market optimism of Ronald Reagan (and Margaret Thatcher). But what is on offer, in response, is a politics of scarcity: right and left share a desire to stop things happening — immigration and imports, in the case of the reactionary right, and economic growth itself, in the case of too much of the progressive left. What we need instead is a politics of abundance. Governments should be encouraged to make positive things happen.

Can Europe Survive? The Story of a Continent in a Fractured World by David Marsh (Yale)

Marsh is one of the most knowledgeable observers of Europe. A former FT journalist and particularly expert on Germany, he describes the crises now confronting the EU and Europe in terms of “four central issues . . . — energy, defence, industry and money”. The book adopts an optimistic tone. But it makes clear how challenging it will be for Europe to thrive in today’s world. If it is to do so, argues Marsh, there must at the least be a close partnership between the EU and UK and a working alliance of both with the US.

The Great Global Transformation: National Market Liberalism in a Multipolar World by Branko Milanovic (Allen Lane/University of Chicago Press)

Milanovic declares that “Nationalism, greed and property define the era of neoliberalism and will continue to define the period of what I have called here ‘national market liberalism’, probably even more so because all three, but especially the nationalistic factor, are globally becoming stronger.” The creation of new forms of property also creates new forms of market power. The need to create more property, in turn, is driven by human greed. Greed in turn fuels nationalism whose aim is to ensure that national wealth is protected and increased. Milanovic, in short, sees the world through a Marxist lens. That makes his thinking both intriguing and original.

1929: The Inside Story of the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History by Andrew Ross Sorkin (Allen Lane)

In 1929, the capitalist ebullience of the “roaring twenties” ended in the Great Crash. In this superb book, Andrew Ross Sorkin of the New York Times brings the great drama to life, by telling the stories of the players. The book is both wonderful history and superb storytelling. But it also delivers a sobering and still relevant lesson. “Could the 1929 crash have been avoided?” asks Ross Sorkin. “The short answer is yes . . . [But the] long answer is that it would have taken almost divine prescience to look beyond the short-term incentives for making money and focus instead on the long-term consequences.”

All this week, FT writers and critics share their favourites. Some highlights are:

Monday: Business by Andrew Hill

Tuesday: Environment by Pilita Clark

Wednesday: Economics by Martin Wolf

Thursday: Fiction by Maria Crawford

Friday: Politics by Gideon Rachman

Saturday: Critics’ choice

The Fractured Age: How the Return of Geopolitics Will Splinter the Global Economy by Neil Shearing (John Murray)

In this compelling book, Shearing, chief economist at Capital Economics, argues that we have been moving towards what he calls a “fractured age” for almost two decades. Donald Trump is a product of this fracturing, not its cause. The turning points were, he argues, the financial crisis of 2007-09 and the rise of China. Trump or no Trump, “The coming decades will be marked”, he argues, “by a deepening superpower rivalry and the fracturing US-China relationships.” In sum, globalisation is coming to an end. This is a depressingly plausible forecast.

The Growth Story of the 21st Century: The Economics and Opportunity of Climate Action by Nicholas Stern (LSE)

Ever since the publication of the seminal Stern Review on the economics of climate change in 2006, the author has been among the world’s most influential thinkers on the subject. In this important book, he brings that analysis up to date. His story is one of achievement, hope and danger. The achievement is a technological revolution, which has turned the then-still-uncertain prospects of cheap, abundant and clean energy into a reality; the hope is of a future that offers prosperity and a stable environment; and the danger is that human folly will reject the achievement and ruin the hope.

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future by Dan Wang (Allen Lane)

Wang, a research fellow at the Hoover History Lab at Stanford, is a Canadian of Chinese origin who has lived and worked in both the US and China. In this superb book, he describes the contrast between the two superpowers whose “competition . . . will define the twenty-first century: an American elite, made up of mostly lawyers, excelling at obstruction, versus a Chinese technocratic class, made up of mostly engineers, that excels at construction”. Each superpower, he suggests, “offers a vision of how the other can be better, if only their leaders and peoples care to take more than a fleeting glance”. At the moment, I fear, the US is imitating Chinese repression without matching Chinese efficiency. That would surely be the worst of both worlds.

Tell us what you think

What are your favourites from this list — and what books have we missed? Tell us in the comments below

For Martin Wolf’s selection of the best economics books from the first half of the year, visit ft.com/summerbooks2025

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café